Chris Reykdal's vision for our schools is blurry at best

/Have you read Superintendent Chris Reykdal’s “K-12 Education Vision and McCleary Framework?”

It’s an 11-page document that Reykdal describes as a “long-term” (six-year) plan for “transformational change” to Washington’s public schools.

But instead of outlining true change, I’m finding Reykdal pays lip service to closing the opportunity gap, using it like a buzzword without sharing any concrete plans to impact it except to reallocate money. He proposes tracking students toward different post-secondary options starting in 8th grade with no safeguards against the discrimination these practices will create in districts struggling to overcome racial bias. He talks of “system redesign” and “fundamental change,” but the crux of Reykdal’s “fundamental change” is to literally add more of the same by lengthening the existing school day, lengthening the existing school year, and offering universal preschool access.

Neal Morton of the Seattle Times summed up Reykdal’s six main proposed changes as:

Provide preschool for all 3- and 4-year-olds.

Add 20 days to elementary and middle-school calendars, and make their school day 30-60 minutes longer.

Start teaching students a second language in kindergarten.

Pay for all high-school students to earn college credit before graduation — and no longer require them to pass state tests to get a diploma.

Create post-high schools plans for every eighth-grader before they enter the ninth grade.

And, of course, 6: Finally resolve the landmark McCleary school-funding case — and Reykdal has some ideas about how to do that.

Let’s start with what I appreciate about Reykdal’s vision.

Universal preschool access is an excellent idea. Especially as Reykdal is guaranteeing access as opposed to making preschool compulsory, he would truly be giving families more choice and more affordable options. I like that.

I also like the idea of teaching a second language starting in kindergarten, and Reykdal says without saying it that the language taught would be Spanish. I wonder how that might play out, but it’s a nice idea, no doubt.

And to his credit, Reykdal’s first paragraph is his most inspiring, so his vision starts strong:

The goal of Washington’s public education system is to prepare every student who walks through our school doors for post-secondary aspirations, careers, and life. To do so, we must embrace an approach to education that encompasses the whole child. In the ongoing struggle to amply fund our schools, we have lost this larger vision. The challenge to amply fund schools to the satisfaction of the State Supreme Court is not the final goal – it is merely the first step in a much larger transformation that will propel Washington state’s K-12 public schools atop the national conversation in quality, outcomes, and equity. In our state’s history we have engaged in this transformative work only a few times. This is a once-in-a-generation moment to redesign our public schools to achieve our highest ideals.

This could be the beginning of everything I’m looking for: preparing students not just for college/career but for life, embracing a whole-child approach, declaring equity to be a pillar, recognizing that McCleary is just a distraction, and acknowledging that transformational change is needed.

But instead of backing this up, it’s mostly milquetoast and money from here on out.

Reykdal considers a McCleary fix to be “the first step in a much larger transformation that will propel Washington state’s K-12 public schools atop the national conversation in quality, outcomes, and equity.” Unfortunately, it’s not often that more money is applied to an inequitable situation with greater equity as the result.

Meanwhile, throughout the document, Reykdal mentions the “opportunity gap” once. He mentions the “achievement gap” once. Here is the only concrete change Reykdal suggests toward closing these gaps, and it’s all about money:

“State-funded turnaround dollars should focus on the schools who experience large performance gaps and multiple gaps across several student demographics.”

So, basically, the monies will flow toward the students we’re failing from a demographic standpoint instead of more broadly to their low-performing schools. That seems good, but again, not an answer — or even anything particularly new. Just a slightly different method of distributing dollars.

I guess that’s not surprising. Reykdal’s vision for the future of education does not include community engagement. He gives no indication that OSPI will be listening to anyone but itself, or that he will be actively soliciting feedback from the students and families most impacted by systemic oppression. He even says as much about his current process: “In thinking about what this might look like, talking to experts, and researching what makes our students successful, I’ve put together this plan.”

He thought about it, he talked to “experts,” and he did research. He did not listen, apparently, to any actual students or families. Then he, a white male politician, wrote this plan to guide our schools from now until my eight-year-old is in eighth grade.

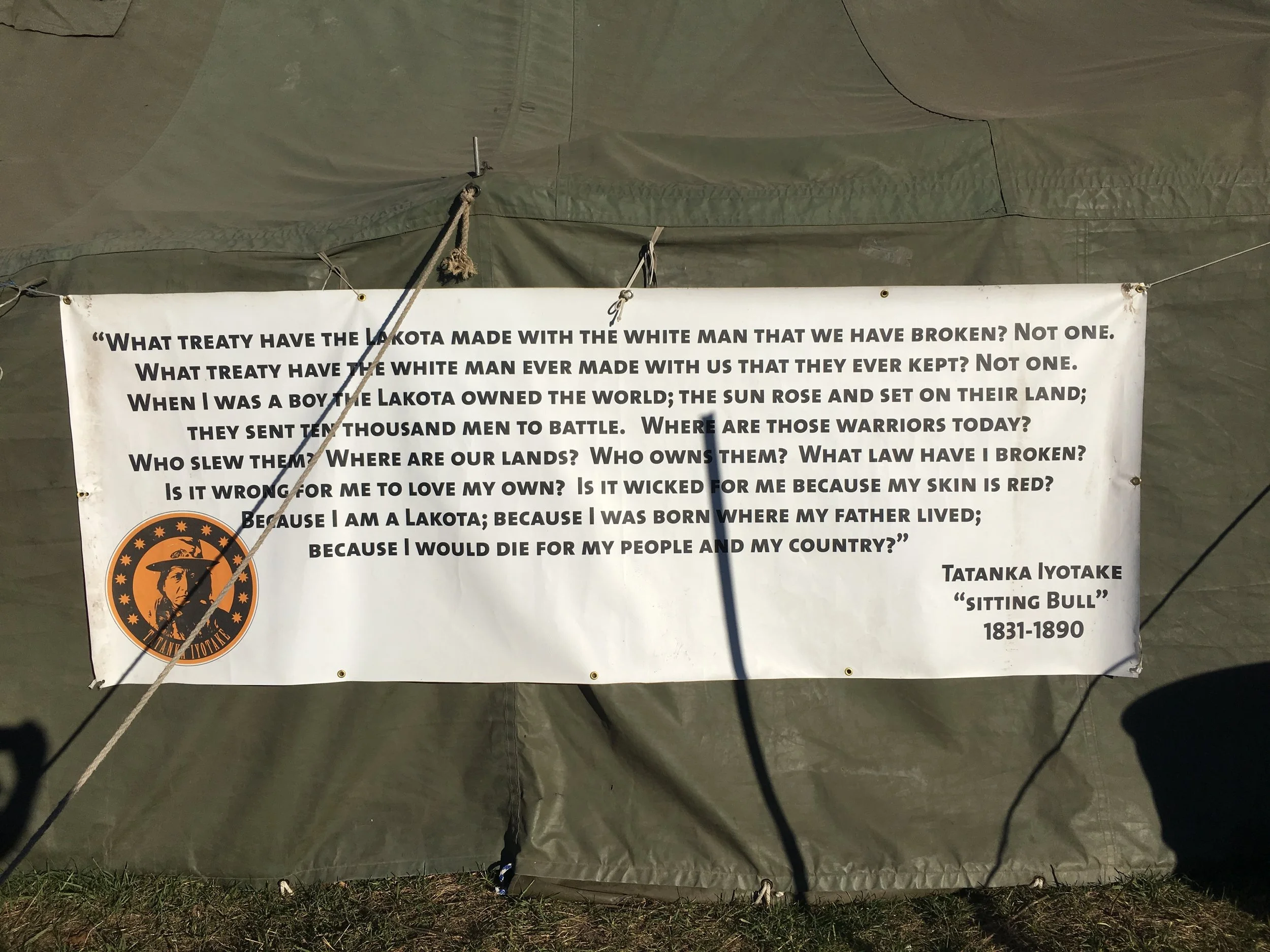

As a result, Reykdal is able to offer only the administrative perspective, and he never mentions any of the many innovative practices being shown nationally to impact opportunity gaps. In his “truly bold thinking,” as he calls it, culturally responsive teaching or ethnic studies never occur to him. He makes no mention of implicit bias testing for teachers, let alone training, or of diversity training for any staff. No mention of bringing more teachers of color into classrooms or of setting high standards for all students.

Instead, he talks about doubling down financially on a public school system we already know is broken, and about tracking kids in eighth grade based on standardized tests we already know produce inequitable results: “In the 8th grade, use the multiple state and local assessments to develop a High School and Beyond Plan (HSBP) for every student.”

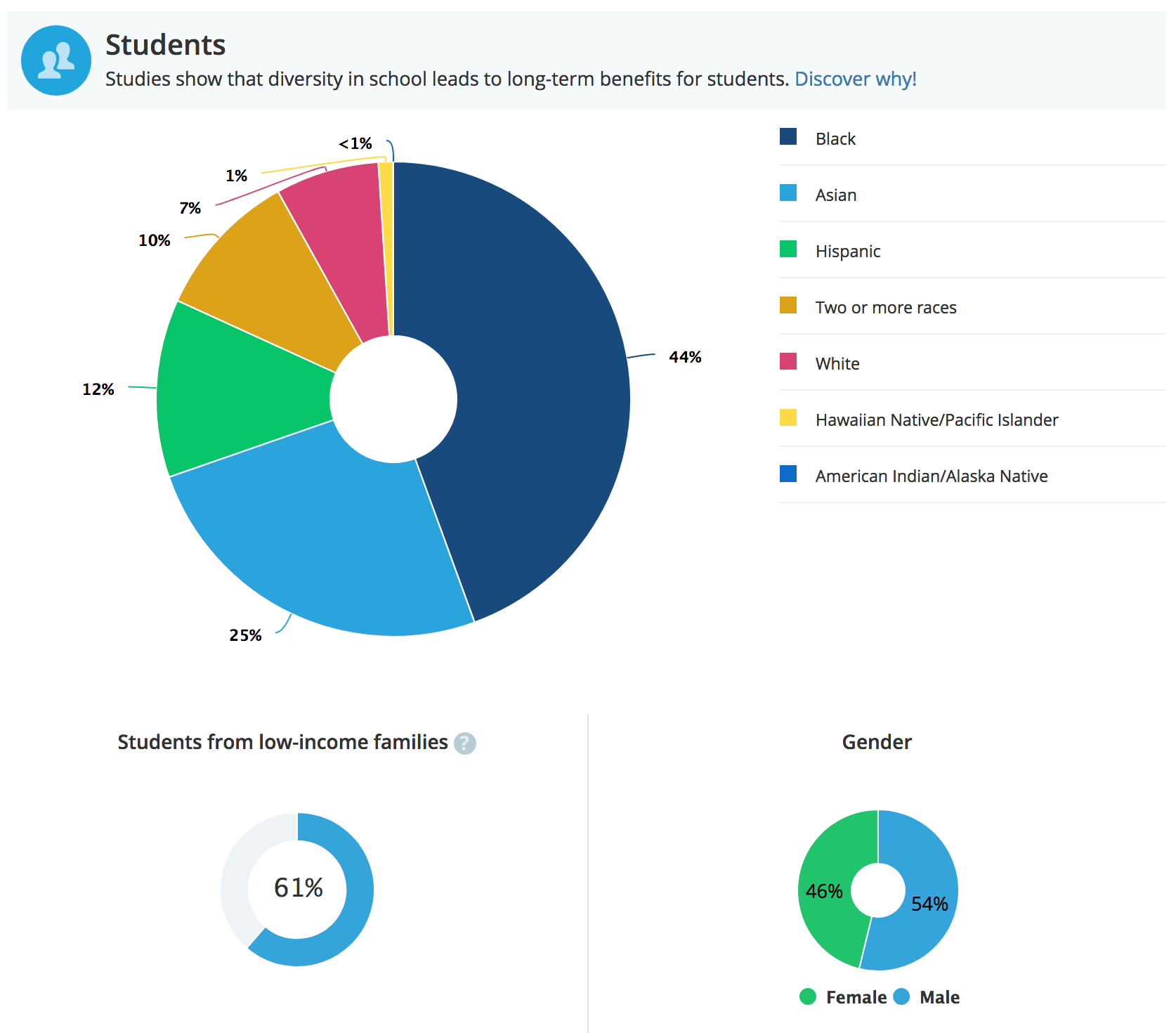

A world exists where this could work out, but in a state like ours plagued by racial and socio-economic inequity in education, this will be executed inequitably. Unless we first provide intense DEI and implicit-bias training for all teachers, counselors and administrators, this will only amplify the disparate outcomes Reykdal claims to want to erase.

Even in the best-case scenario, it creates a culture where low expectations are allowed for some kids and not others. The kids are all capable. Yet Reykdal proposes to limit their future opportunities based on their past. That’s hardly cutting-edge.

My sense throughout last year’s campaign was that Reykdal was more interested in being a politician, in eventually being able to take credit for having fixed McCleary and fully funded our schools, and this vision of Reykdal’s seems to fit that profile.

He closes with this:

“We are in a highly competitive global economy and that means gleaning the best practices from around the world in our redesign. Success looks like a longer school day, a longer school year, substantially better compensation for our educators and support staff, and a completely new approach to developing globally successful students.”

That’s what success looks like? Based on what?

Is Reykdal really saying he’ll consider this a success if our kids spend more time in school, and the adults are better paid? Because he has not suggested anything resembling "a completely new approach" to education.

Shouldn't success look like empowering kids to grow faster and achieve more in school and in life? Shouldn't it be teachers that feel valued and push themselves to get better and better? You can lengthen the school days, but it doesn't guarantee students will learn more. You can raise teacher salaries, but it doesn't guarantee they'll teach better. Reykdal’s definition of success strikes me as one that doesn't move the needle. It’s certainly one that doesn’t take any risks.

How can we expect to close the opportunity gap without giving any kids any new opportunities? More instruction hours and more days in class will only produce more of the same if things haven’t fundamentally changed, and despite the number of times Reykdal tells us everything will be fundamentally different, his vision for the future is just more of the same, too.

That’s not good enough. Not when the status quo is already leaving so many kids high and dry.