I was lucky enough to participate in the first Indigenous Peoples March in Washington DC on Friday. Listen to the sounds that surrounded me and join me in considering your place in all of this.

Read MoreOur Lives on this Earth: A Story of Soul Connecting with Spirit

/By Ryan Flesch

It was Nov. 6, 2016. I had spent three months following the Water Protectors camping out in the Standing Rock reservation in North Dakota on social media, and listening quietly to the intellect of my heart. My heart wanted me there, so I posted to social media: “I have spent too much time sitting in the comfort of my own home saying to myself that something I see is wrong. I'm getting up and I'm going to Standing Rock to show my support with my life, not the share button.”

Read MoreThe Rise Up and Be Recognized Awards: Honoring a Handful of 2017's Local Heroes

/Welcome one and all to the first semi-annual, fully manual Rise Up and Be Recognized Awards. Thank you for being here, wherever that may be.

These awards were created by me as a way to recognize a handful of Washingtonians who deserve a few extra hand-claps for the way their work and their way of life contributed to positive change in 2017.

The judging process was stringent and unscientific. I created the categories to suit my fancies, and I’ve awarded fake awards to whatever number of people I please. By the end, I’ll have failed to mention just about everyone, so if you find you've been omitted, don’t despair. The pool of nominees was limited to people I know about and managed to think of while writing this, and as a periodic shut-in, that’s not as long a list of names as you might think. For instance, I only finally discovered a few months ago that Chance the Rapper is amazing, if that gives you some idea. So, if you or someone you know has been egregiously overlooked, please get in touch with me and I’m sure I’d be happy to make up some new awards in the near future.

Read MoreReflecting on love of family and love for our city as an urban juror in Seattle

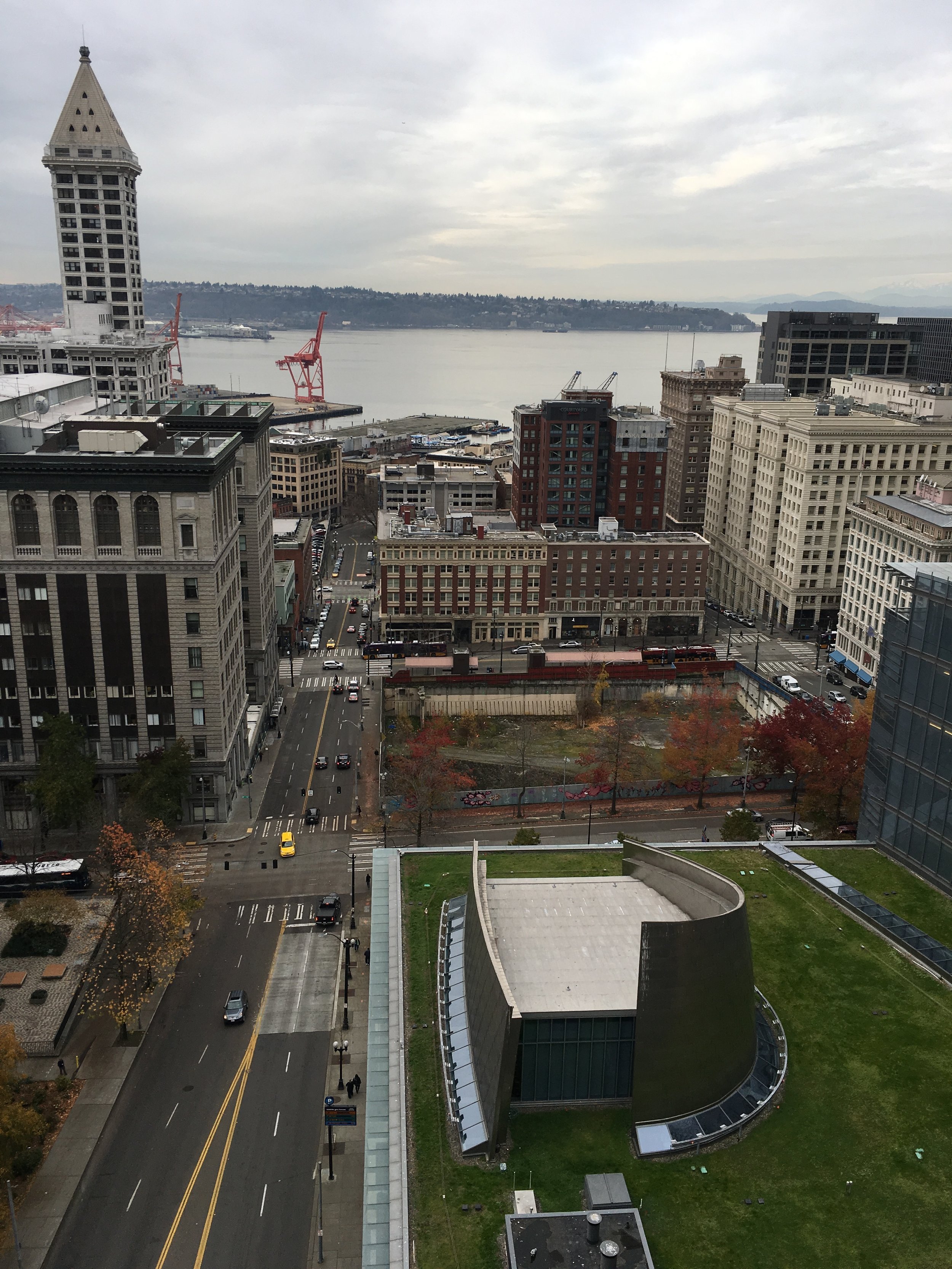

/I was called for jury duty this week. Municipal Court of Seattle.

In fact, as I type this, I’m sitting on the 12th floor of the downtown courthouse building awaiting juroral deployment… as I have been doing continuously since 8:30 this morning. It’s been a boring day so far, but it’s nice to have been bored in a warm, beautiful room, if nothing else, watching the sun creep toward the horizon over the Sound. This is my view currently:

I’ve had plenty of time alone with my thoughts today, and I’ve reached a conclusion: in writing this blog, in focusing on the inequities in Seattle’s schools and communities, I tend to live in a fairly negative head-space when it comes to thinking about my home, about the city where I’m raising my family.

For one thing, that’s not a good way to live. It’s exhausting. Literally depressing, in fact.

But it’s also not an accurate reflection of how I really feel about Seattle. Sure, it’s dark, it’s damp, it’s segregated, and it’s got its share of issues. But it’s also a place of rich beauty, both in terms of the extravagant natural beauty that sandwiches the city and of the interpersonal beauty within it.

I find it’s easy to take for granted the ways that our city and our state — and us, its people — are kicking ass.

We’ve been on the front lines in recent years when it comes to putting our legislation where our “liberal” mouth is. Gay marriage, charter schools and cannabis are all legal, and we’ve taken nation-leading stances against discriminatory laws targeting immigrants and LGBTQ folks.

It’s extremely common now to find gender-neutral bathrooms in Seattle, and a huge number of businesses, restaurants and coffee shops proudly display a commitment to providing safe spaces. This, in contrast, was a sign I encountered in a bathroom last fall in in Miles City, Montana:

We’ve done all kinds of courageous, radical things lately. Water protectors in the South Sound last year shut down a train attempting to transport supplies to Dakota Access Pipeline (DAPL) work sites. We felt the ripples at the time in Standing Rock, and it was powerful.

Seattle divested its public funds from Wells Fargo as a matter of principle a few months back. We are at the vanguard of the movement for fair wages. Activists across the city successfully halted government plans to build a new youth jail. We even had a glimmering moment earlier this year when it looked like we might elect Nikkita Oliver as our next mayor.

And let's not forget there's a baseball team here, which is important for morale — even if, let’s be honest, it’s the Mariners. No offense.

It’s strange how easy it can be to overlook these sorts of things when so much else seems to be crumbling around us. Along these same lines, I spend a lot more time focused on the negatives at Emerson Elementary, the neighborhood public school where we send our oldest son, than I do on the positives.

Now, I’d argue that this is a rightful imbalance, and that I’m not denigrating (I hope) the school or community as much as I am advocating for more resources and attention at an institution that has been long overlooked. But it still means I regularly spend hours looking at a computer screen through the opposite of rose-colored glasses as I write about my son’s school, his district and our home.

It’s weird.

Emerson is a beautiful place, too. My son walks every day into a cool old brick school building with a view of Lake Washington from the second-story library. The student body could hardly be more diverse, and we are lucky that the school is filled with similarly diverse, committed teachers and staff.

My son’s teacher is fantastic. She sees and values him as a whole person, and when she’s gone, he misses her. He’s learning, he’s comfortable, he’s happy and he’s safe. That’s most of what I could ever ask for out of a school right there. Well, no. But it’s most of what I currently ask for out of a public school, and that’s pretty good.

We’re getting close to that time of year when we start making resolutions, mapping out all the new ways we’re going to start living when the calendar flips. At the top of my list is to appreciate all of the good and beautiful things in my life, starting with the time and love I am so lucky to share with my kids and my partner, and with the beautiful home we share that helps make it possible. All things, it seems, stem from there. I hope, then, as I write and advocate and live through the coming year, to remember that the strength and will to fight against these systems and tools of oppression comes from a place of love.

I write so often about Emerson because I love my son. I write so often about Seattle because I love my family, and I love our city, and I know we can do and be even better.

I write about privilege because I love my life, and because the open doors and loving second chances I’ve been handed over and over should be for everyone.

I’m sure I’ll still spend next year shouting from the rooftops yet again, riled up about inequity and angry about systemic oppression and overt racism and latent bias and about the ways they infect our schools and our lives, and I’ll still be as committed as ever to holding us and our city to an unrelenting standard.

But I do it out of love.

So, that’s my resolution. I’ll keep breathing in the smog and the smoke and the greed and the politics and the racism and the classism and the division and the hate. I’ll breathe it in, filter it out, and exhale it back into the world as love, whatever form that takes.

The Indian Removal Act was signed on this date in 1830. What does it mean today?

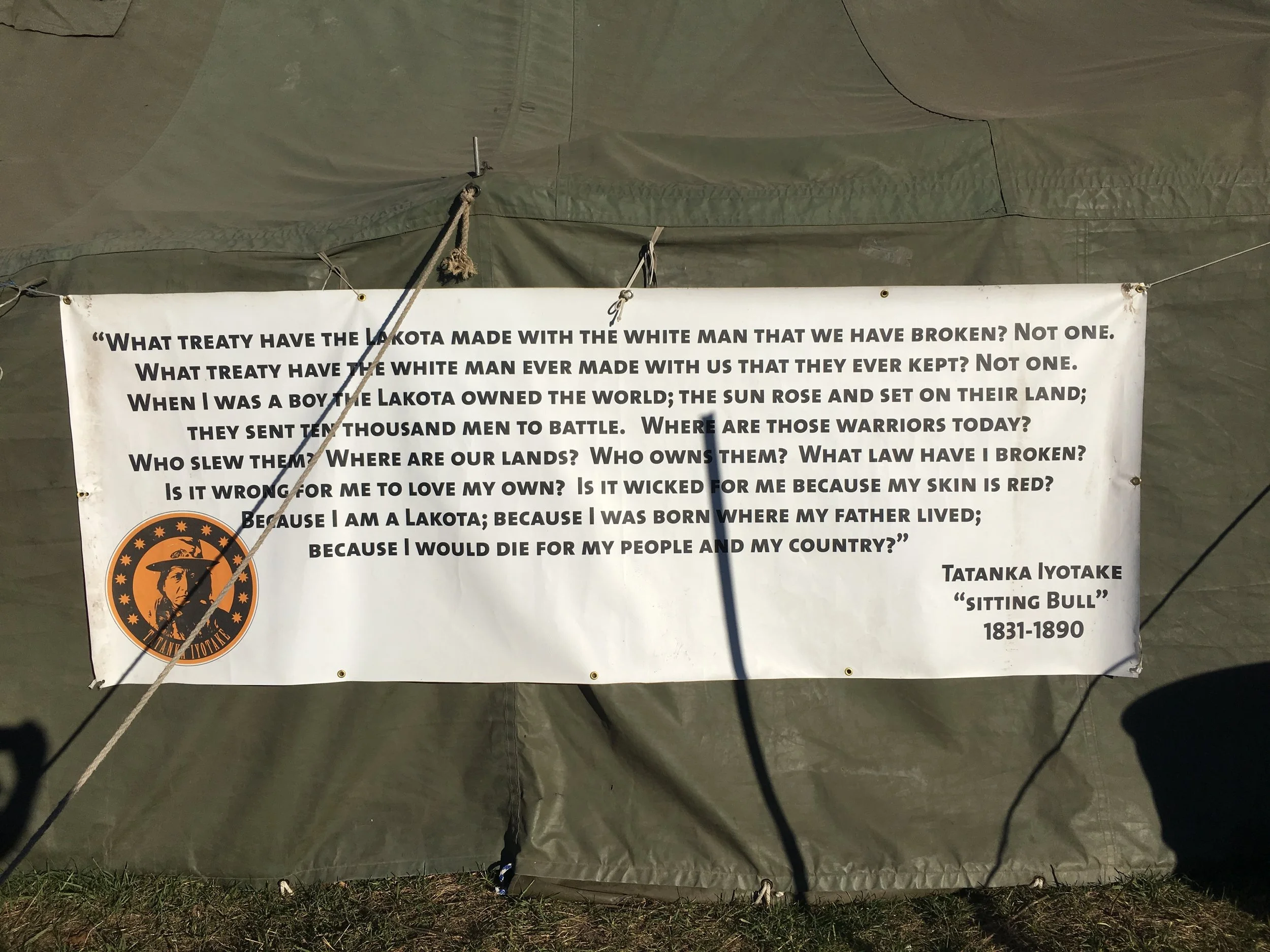

/A sign hung on the side of a tent at Rosebud Camp on the Standing Rock Sioux Reservation in November 2016.

Today is an important anniversary to remember. It’s not one to by any means celebrate, but neither is it one we can forget.

On May 28, 1830, U.S. President Andrew Jackson signed the Indian Removal Act into law.

According to the Library of Congress, this “allowed the president to grant unsettled lands west of the Mississippi in exchange for Indian lands within existing state borders. A few tribes went peacefully, but many resisted the relocation policy. During the fall and winter of 1838 and 1839, the Cherokees were forcibly moved west by the United States government. Approximately 4,000 Cherokees died on this forced march, which became known as the ‘Trail of Tears.’”

From the U.S. Office of the Historian:

In his 1831 ruling on Cherokee Nation v. the State of Georgia, Chief Justice John Marshall declared that “the Indian territory is admitted to compose a part of the United States,” and affirmed that the tribes were “domestic dependent nations” and “their relation to the United States resembles that of a ward to his guardian.” However, the following year the Supreme Court reversed itself and ruled that Indian tribes were indeed sovereign and immune from Georgia laws. President Jackson nonetheless refused to heed the Court’s decision. He obtained the signature of a Cherokee chief agreeing to relocation in the Treaty of New Echota, which Congress ratified against the protests of Daniel Webster and Henry Clay in 1835. The Cherokee signing party represented only a faction of the Cherokee, and the majority followed Principal Chief John Ross in a desperate attempt to hold onto their land. This attempt faltered in 1838, when, under the guns of federal troops and Georgia state militia, the Cherokee tribe were forced to the dry plains across the Mississippi. The best evidence indicates that between three and four thousand out of the fifteen to sixteen thousand Cherokees died en route from the brutal conditions of the “Trail of Tears.”

When our government was established, it operated on a system of slavery and a burgeoning belief in “manifest destiny” as justification for genocide of indigenous people.

By 1830, our president was still a slaveowner, and he signed a bill that allowed him to sign treaties never intended to be kept even more freely than before.

Fast forward 183 years, and I can't help but ask what the government has done in that time to earn our trust. More than finding reason to believe in the possibility of tomorrow, I find I'm starting to lose hope.

An article published yesterday by The Intercept, for instance, reveals through public records requests and leaked emails that Energy Transfer Partners, the corporation building the Dakota Access Pipeline, hired a private mercenary firm to work directly with the FBI, BIA and various levels of federal, state and local law enforcement to conduct illegal surveillance and to treat peaceful #NoDAPL demonstrators in Standing Rock last year as “terrorists” and “rioters” on a “battlefield.”

I might be crazy. I’m aware of that. But in a conflict of interest between a for-profit corporation and an organically formed group of people (mostly U.S. citizens), the United States government acted with military force on behalf of the corporation. It's just one of many examples of this phenomenon. What does that mean?

It happened while Obama was in office, and it’s continued with Trump. It's neither a partisan issue nor a new one. What does that mean?

And what does it mean for our kids that we’re sending them to schools made mandatory by this same government? I know that’s a crazy-sounding question in the “normal” world, but it’s one I again can’t keep from asking.

And apparently I'm not the first to ask it, because it’s also one that Malcolm X may have already answered: “Only a fool would let his enemy educate his children.”

Our government has shown throughout history a perfect willingness to treat its own citizens like the enemy. Does that mean we’re fools for thinking we’ll ever find what we’re looking for in their schools?

Standing Rock descends on the White House with sage and ceremony

/It's true, what they say: You get used to being cold. It doesn't take all that long, either. One month on the prairie and I barely noticed I was shivering all the time in the constant sodden chill; I was used to the dull ache in my throat and eyes as my sinuses clogged and unclogged, used to never getting fully undressed, to changing one bit of clothing at a time, hiding under blankets.

It was only fitting that the Native Nations Rise March took place on a freezing, blustery wet day in Washington DC, when just the day before the temperature had neared the seventies. It was as if the tribes who had flooded the capital en masse, arriving by bus and carpooled ride, by plane and train and truck, had dragged the wind-whipped prairie to the Capital with them, perhaps to accentuate the profundity and raw elemental nature of the struggle they faced at Standing Rock. The cold has never deterred the resilience of the First Nations people to fight for the Earth, and it did not this day in Washington, either.

Over 5,000 Native Americans and their allies showed up to walk down the road to the white house, beating drums and dancing and burning bundles of sage. The air was filled with smoke, and with song, prayer, and chants:

"You can't drink oil; keep it in the soil!"

"We exist! We resist! We rise!"

And of course, always, "Mni Wiconi!" Water is life.

As we made our way to the National Mall, I glanced up at the suited men and women peering out the windows of the high rises, small groups of them gathered to watch the long train of people march by with our banners and drums and the puppet of the black snake, which weaved through the crowd held aloft on several sticks. I wondered what the people up in those windows were thinking, and if they always stared like that when there was a demonstration taking place, or if there was something special about this one. Something exotic and otherized in the bright colors and burning bundles of herbs.

The way they stood, gawking, made me think about how this country has always treated Native Americans: fetishizing their clothing, culture and looks, bestowing the pigeon-holing archetypes of the "Noble Savage," and at the same time stripping their basic human dignities and long-written land treaties, subjecting them to literally hundreds of years of systematic environmental racism.

Photo by Jacq Williams.

I thought about how this march, the people who braved the prairie winter, this whole long and harrowing fight, was about violently forcing Native Americans to accept something that was deemed too dangerous for white people. I can't stop coming back to that, through all of this.

We marched.

We marched to Trump Tower, where on the front lawn the Sioux erected a teepee, and small groups of women danced, while the men drummed and prayed as they symbolically reclaimed the stolen land of their people. I stood on a bench to see protectors snaking around blocks in either directions, dozens of tribes represented, thousands of flushed and sniffling faces who came streaming into the streets from the warm comfort of their lives to stand up for the sacred. Just as they had done at Standing Rock.

I was starting to run into more and more people I knew from camp, people we fed in the kitchen, people who taught me songs and told me secrets, and who came into our yurt at night looking to swap histories. I hugged and laughed with people I was desperate to see again, children and the women who herded them down the slippery hills at camp, the head of security, and the people who built the school among them. I knew half of them had ridden buses for days to be here. Their faces made me ache to be back on the prairie, where we interacted in such an unadulterated and archaic way, never buried in our phones or dogged down by the necessity of exchanging dollars with one another. We learned more about each other than best friends know, having to be present and integral in one another's lives from the very beginning. Having no other choice but to work together.

We marched on, to the front gates of the White House, where I doubted the President cared enough to glance out of the window, had he been there at all.

It's a strange feeling, resisting in such a forthright and visual way, fighting for what you know is your life and the lives of your children's children, and knowing the lawmakers and lobbyists of this country have the option to just look away. The people in power, and the people at home, who don't visit news sources which would even cover something like this march, can still doze in comfort while we scream in the face of willful ignorance.

Photo by Jacq Williams.

The Water Protectors gathered at the White House fence, chanted and held banners, and were told to get off of the sidewalk by the police and secret service, over and over again. We took pictures and burned more sage, and some people called out to the police: "Join us! Your grandchildren need clean water, too!" They were met with the blank stares of unabashed indifference. To them we were merely a possible security threat, to be assessed, addressed, dismissed.

My small group broke off and made it to the rally on the lawn. We hung around the outskirts, and were glad we did, as Dave Archambault's voice was the one we soon heard over the surrounding speakers. DAPL Dave, as he is called, is the Chairman of the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe, and it is widely believed that he made a deal with Energy Transfer Partners and the BIA to dismantle the camps—even those on the private property of Ladonna Allard—and essentially smooth the way for the pipeline's completion.

Those who didn't know about this cheered him as his spoke his message of unity. Those who did, like Ladonna's daughter, Prairie, stood in the back and shouted their discontent. I felt the splintering, just like I had at camp, of the reality of the situation versus the perception.

The reality, I have come to understand, is that we were never going to stop a 3 billion dollar pipeline from being completed. Not in a capitalist society which places the monetary value of commodity over life in all its forms. We were there operating under the perception, the hopeful belief, that the will of millions of Americans and the thousands of people who showed up to represent them, were enough to convince the world that the sanctity of our Native Tribes— their sacred land and their drinking water—are of more value than another faulty pipeline meant to carry oil which wouldn't even be used for American consumption. Essentially, that water/life was more important than oil/money.

We were wrong. Despite the best of our efforts, the black snake has been built and will carry highly volatile fracked oil as early as next week.

But that doesn't mean that it was futile to gather on the prairie or flood the streets of Washington. All else aside, I don't know one person who returned home from the protest in North Dakota without a profound sense of purpose and empowerment, and a deeper understanding of the intersectionality of our resistance. Knowing, down to our marrow, that while we shout for the water we are also shouting for racial equality, environmental justice, and the reconfiguring of an economic system which keeps defense contractors buying islands while children starve on our own soil.

Gathering like this, making camp and forming community in the face of capitalist greed, flooding the streets of Washington in winter, are in themselves acts of profound defiance. Going back to our own lives with the seeds we took from these gatherings, and planting, cultivating, and redistributing the crop amongst ourselves— that is an act of revolution. To reconfigure a pyramid-shaped system which has forever only benefitted the top, we need people on the ground who have already chosen to live a different way, who are willing to drop everything to come together in rejection of this wildly inequitable structure, to break down the pyramid and use the stones to build well-trodden paths from house to house.

Standing Rock, and the Native Nations Rise March on DC, have proven that we have those people. That we are willing to brave the elements and our own self-doubt in order to return to a more harmonious, communal, sacred way of life, and that our numbers are growing. The truth is this: among the sleeping souls of complacency, there is an awakening of warriors for a new world who are ready to resist, and to re-imagine. At a moment's notice, ready to rise.

Jacq Williams is a freelance writer, homesteader, and activist from Southeast Michigan who spent several weeks at Sacred Stone Camp in Standing Rock in the fall and winter of 2016. She is currently working on an advocacy project for pregnant women in prison and transitional housing, called the Inmate Birth and Infancy Project.

How to Bring the Lessons of Standing Rock into the Classroom

/Photo taken by Matt Halvorson on the Standing Rock Reservation in November 2016.

Amid the recent executive order expediting the construction of the Dakota Access Pipeline on the Standing Rock Reservation, teachers inside and outside the community must continue to engage their students and reflect on both its impact and historical context.

The movement to protect the sacred lands of the Oceti Sakowin (the Seven Council Fires of the Lakota, Nakota, and Dakota Nations) not only united a network of tribal nations and allies, but also sparked long overdue—and sometimes difficult—discussions on a multitude of complex issues, including environmental protection, tribal sovereignty, racial oppression, privilege, and access to power.

While the Sacred Stone Camp has been disbanded, teachers can still engage students in this dialogue and keep this issue—and the history of Native people and lands—in the national consciousness. Below are some resources and suggestions for teachers to leverage now:

Photo taken by Matt Halvorson on the Standing Rock Reservation in November 2016.

- Get the facts. Discover the historical context of the events leading to Standing Rock with this brief primer from KGW-TV in Portland and a more detailed version from NYC Stands with Standing Rock titled the #StandingRockSyllabus.

- Understand firsthand perspectives. Read an account of the protests from Robert Cook, who leads Teach For America’s Native Alliance Initiative. Also be sure to visit an inspiring piece from Tariq Brownotter, a senior at McLaughlin High School in South Dakota who ran more than 500 miles from South Dakota to Washington, D.C., as part of a Dakota Access Pipeline Awareness run. The Washington Post and National Geographic have more voices from the Sacred Stone camp. (RUFS Note: read more about Matt Halvorson's experience at Standing Rock on the Rise Up For Students blog)

- Create a powerful lesson. Several news organizations have put together downloadable lesson plans that cover the conflict from a variety of viewpoints in both print and video, including National Geographic, The New York Times (here and here), and KQED-TV, San Francisco’s PBS affiliate. Aside from news outlets, check out this page from Teaching Tolerance, a project of the Southern Poverty Law Center, which offers ways for educators to make Standing Rock accessible to students across a range of subjects.

- Teach stories of youth activism. You can also view a collection of resources from The Choices Program, which focuses on youth activists’ role in this and other social movements.

- Stay engaged. Learn more about organizations advocating for the rights of Native communities:

- Native Organizers Alliance: Website, Facebook

- Thunder Valley: Website, Facebook

- Water Protector Legal Collective: Website

- Indigenous Environmental Network: Website, Facebook

- Indigenous Peoples Power Project: Website, Facebook

- Honor the Earth: Website, Facebook

- Brave Heart Society: Facebook

An original version of this post originally appeared on TeacherPop. Reposted with permission.

Brought to you by Teach For America, TeacherPop provides real talk, tips, and activities that teachers can use in the classroom. Writers offer advice for all of the challenges new teachers face, sharing everything from difficult reflections on their darkest days to quick tips for sprucing up their classrooms and their lives.

Signs of Hope in South Seattle

/I wrote earlier this month about the many different positive messages people have posted in their yards in my neighborhood, and how there's some power in these quiet, steady displays of love.

I accidentally drove down a side street off McClellan a couple days ago and saw the same style of Black Lives Matter sign in almost every yard. By the end of the block, I was choked up. Granted, I'm pretty easily weepy these days, but still, it made me wonder: what if the whole city looked like that? I bet that's what a sanctuary city would really look like.

Hate has no home in the 98118

/I'm back home again in Rainier Beach after a whirlwind six-day trip to and from the Standing Rock Sioux Reservation in North Dakota, and I'm filled this week by appreciation for my neighborhood.

The 98118 zip code is known to be "the most diverse zip code in the nation," and that diversity is reflected in the messages on the yard signs decorating the blocks.

In just driving a few minutes around our neighborhood with my sons, we found more signs demanding social justice and declaring solidarity than we had time to photograph. Here are just a few:

"Black Lives Matter"

"Silence = More Deaths"

"Stop profiling Muslims."

"Refugees are welcome here."

"No matter where you're from, we're glad you're our neighbor."

"Here we believe love is love, no human is illegal, Black lives matter, science is real, women's rights are human rights, water is life, kindness is everything."

These are bold words sending powerful messages at a time when we need them most. What messages are you sending?

What messages are you seeing around you? Do you have photos to share?

#BlackLivesMatter

#NoDAPL

#WaterIsLife

#ScienceIsReal

#NoMuslimBan

With largest #NoDAPL camps evacuated, Standing Rock picks up the pieces

/I drove back to the #NoDAPL camps at Standing Rock this week.

The Army Corps of Engineers in conjunction with Morton County Law Enforcement issued a deadline of 2 pm Wednesday (Feb. 22) to clear the Oceti Oyate camp (formerly Oceti Sakowin), which sits on contested land, as well as Rosebud camp and part of Sacred Stone, both of which are (were?) on the Standing Rock Sioux Reservation but below the flood plane.

I wanted to be present for the deadline, to do what I could to help, and right at 2 p.m. I found myself in the Oceti camp in a pickup truck trying to find two kids who we’d been told needed to get out (and they did).

Two water protectors look out over the evacuated Oceti Oyate camp (formerly Oceti Sakowin) as the 2 p.m. eviction deadline ticks past on Feb. 22, 2016. Photo by Matt Halvorson.

The strange thing, though, was that the police were not particularly aggressive in clearing out the camp. They arrested either nine or 10 people Wednesday, depending on which report you read, and I’m told that something like 50 more were arrested the next day when the police came back through and fully cleared the camps.

The police tried to intimidate and definitely inflicted some physical injury, but all in all, the eviction was surprisingly peaceful. It only takes one police officer responding with too much force too quickly, or one person reacting too strongly to seeing his grandmother being handled by the police for violence to erupt and turn a situation like this into a disaster.

Instead, it was peaceful-ish, as policing goes. Or if peaceful isn’t the right word, well, nobody died. The police were not startlingly violent toward the water protectors who chose to stay in camp and pray until the end, which is what I was afraid of. But then, the #NoDAPL movement has never been characterized by fatal violence.

Set aside for a moment the grotesque images of water cannons, rubber bullets and explosives used by police in riot gear in Standing Rock.

During the protests in Ferguson of the past few years, militarized police frequently shot real bullets at Black Lives Matter protesters and occasionally killed them. Even when the PR risk should have steadied their trigger fingers, fatalities were commonplace. On the one-year anniversary of Michael Brown’s murder, for example, St. Louis Police shot and killed another young black man during that night’s protest.

In Standing Rock, on the other hand, through more than 10 months of steady demonstrations and consistent police confrontation, not one water protector was killed. The police inflicted serious injuries and committed atrocities, but everyone survived.

This has been on my mind for months but hasn’t been something I’ve known how to talk about, partly because I was in Standing Rock bearing witness to much of the police violence that has made the news. And it was painful and traumatic and frightening. But I also made an appearance in Ferguson, and I know that the stakes were more immediate there, though no higher in the long run.

I don't know what it means. Our government and law enforcement certainly have a deep and storied history of killing indigenous people. They just haven't done that in Standing Rock yet, even as they're doing it elsewhere. Maybe it just means that our oppression of people of color has been tailored to each specific community.

Whatever the case, just as happened on Dec. 4 last year when the Army Corps under the Obama administration denied the easement needed for Energy Transfer Partners to complete the Dakota Access Pipeline, this is a time of change and transition for the #NoDAPL camps. Roughly 600 people remained in the camps from mid-December through mid-February, and only a handful of reinforcements arrived this week.

Now many of them are heading home. Many more are staying and continuing the fight on the ground in North Dakota, and a group of committed indigenous activists have promised to continue finding new sites for prayer camps to continue if needed. LaDonna Brave Bull Allard, who owns the Sacred Stone land and founded the original camp last April, has vowed to maintain a community on her own land as well, come figurative hell or literal high water.

And everyone who is leaving is leaving profoundly changed, it seems, carrying with them a sense of invigorated spirituality and an empowered sense of capability and responsibility to stand up more fiercely than ever to injustice.

Perhaps my greatest takeaway has been the interconnectedness of movements that had remained, until now, disparate. The issues being raised by #NoDAPL water protectors, indigenous rights advocates, environmental activists, Black Lives Matter protesters, immigrant rights groups, education advocates, workers' rights groups and countless others are all symptoms of the same disease, branches of a tree whose trunk contains the sickness of capitalist greed, colonial entitlement and systemic inequity.

I see the possibility for enormous breakthroughs as our passions are shown more clearly to have a common enemy, and as it becomes harder to ignore that our own liberation is dependent on our neighbor’s.

We’re all in this together — even the police officers and DAPL employees who are following orders in order to maintain an income they’re afraid to lose. Even Trump and everyone who voted for him. We are protecting this water for everyone. We are shouting for everyone’s sake that Black Lives Matter -- not just for the Black men and women who face the greatest immediate risk -- because no life is truly valued by a society that declares some expendable. We are demanding equitable access to high-quality public education because its absence leaves a cavity in our country and our communities.

No matter what you hear in the mainstream media, the #NoDAPL movement isn’t ending. It’s just shifting, dispersing, expanding. Water falls from the sky as millions of individual drops, but those beads of water don’t remain separate. They can’t help but combine, to join together as they touch, and in doing so, to become a roaring, powerful body of water.

We, too, seem like millions of individuals, but we come from the same source, whatever that is. We are intrinsically connected. And when we act out those connections, they deepen, and we awaken the potential of our unified power to overwhelm the hate and division that plagues us now.

As Trump tries to get DAPL finished, Standing Rock responds: "We are just now beginning this fight"

/Donald Trump has signed executive memoranda to authorize the Dakota Access and Keystone XL Pipelines.

I spent a month at Standing Rock near the end of last year. The violence visited by militarized police on peaceful everyday people was shocking to see up close.

As intense and vivid as the encounters were with armored police, the more surreal aspects have been even more jarring to me in the long run. What does it mean that they were there, enforcing a corporation’s desire for profit against a peaceful assembly of real-life citizens? What does it mean that the government never fully intervened, even under Obama?

LaDonna Brave Bull Allard is a member of the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe, and she owns the land on the reservation that borders the much-discussed land controlled by the Army Corps of Engineers. The original camp of water protectors, Sacred Stone, from which the entire #NoDAPL resistance grew, continues to sit on LaDonna’s private land. She has essentially been hosting everyone who has come to Standing Rock and stayed at the camps.

She posted a video on Facebook today addressing the many conflicting reports and the unrest that has grown out of Trump’s DAPL memo. Here is the full transcript:

Good evening, everybody.

I wanted to tell you, it has been a long day. A lot of things have happened.

We started this day with the United Nations listening to testimony on the water protectors and all of the events that happened to our water protectors. Today was hard, listening to the people who were hurt, the damage they received from Morton County Sheriffs and Army National Guard as they stood up for the water.

But while we were hearing the testimony, we heard the decision from president trump on signing the executive memoranda — they are not executive orders yet, they are executive memoranda — for Dakota Access and XL Pipeline.

We knew this day was coming.

We are asking everybody to say prayers today to give the people who are standing strength — wherever you are, to pray.

We have started something that we must complete, and that is the healing of our nations. That is the healing of our people.

And how do we do that? We stand up for the water. We continue to stand up for the water. And so I’m asking you to continue to stand with me. Continue to stand for the beautiful rivers, for the beautiful lakes, for the beautiful creeks. Everywhere our water flows, please stand.

We are just now beginning this fight.

My heart hurts for all those that are hurt, all those that have suffered. But I see something in each one of them. I see this strength and this pride. I see a building of a new nation, and so even as we start this new journey, this new fight — because that’s what it is — we must all stand together.

And we will continue to stand, because I will continue to stand.

I will not back down.

I will not back down. We must stand for the water. We have no other choice. When we stand for the water, we stand for the people. We stand for the people, we stand for healing of our nations. It is time for all the nations to be healed.

So, I wanted to let you know that we continue to stand. I know there’s a lot of confusion out there with the proposed closing of the camps — or not closing of the camps — who has jurisdiction? — all of these things.

Sacred Stone is not closing. We’ll be standing. And we ask you to continue to stand with us. All of you are welcome in my home and on my land. You are welcome to come back and you are welcome to stand with us, because we will continue to stand.

Be safe, everyone. Pray hard, because the journey has just begun.

Donald Trump is doing so many dangerous, awful things so quickly that we can't afford to spend any time wondering what to do.

However bad things have been, however unfair, however inequitable, however racist, however sexist, however dangerous Amurrica already was… it’s worse. Trump has his foot on the accelerator of the DeLorean and we are screaming at 88 mph toward the alternate timeline where Biff has the almanac and everything is disgusting and awful. (In fact, Trump might be Biff with the Almanac. I’ll look into that more soon.)

This is what it's like to use a port-a-potty during a blizzard in North Dakota. Photo by Lindsay Hill.

My friend Nic Cochran has been in Standing Rock throughout this brutal winter. He would love to go home and be warm indoors back home in West Virginia. He's tired. He acknowledges this. And he called Trump's memorandum "an executive order to stay."

The time is now for all of us everywhere. It’s like every movie. Goodness is under assault, truly. Find a way to stand up against it. Be brave. Be safe if you can, but be brave no matter what. Safety isn’t an option for everyone.

Here's an easy place to start. Join Seattle's visionary leader, Kshama Sawant, who has helped organize an action on Feb. 11 to demand that the Seattle City Council boycott Wells Fargo until it withdraws its DAPL funding: Stop Trump! Boycott Wells Fargo, NoDAPL!

Day 7 at Standing Rock: Judgement Day

/About the Music: “Judgement Day”

From the musician, Cee Goods:

The energy feels like it's coming soon. People are going to have to make conscious decisions of how they want our future to look. Are you with good? Or are you with greed?

An old Lakota prophecy says that a black snake will tear through the continent, ravaging the Earth and endangering all life on the planet if it is allowed to take hold. Similar prophecies exist across many different tribes, as do foretellings of the importance of the Seventh Generation in defeating the serpent and preserving life on Earth.

Many believe that the Dakota Access Pipeline (DAPL) is the fabled black snake.

I have gotten to know a number of strong, proud, brilliant young Lakota men and women during my time here. They're a little younger than me, which makes them part of the seventh generation of their people to be born since their first contact with white European invaders. I'm not alone in sensing the power that flows through them from their ancestors. If you met them, I think you, too, would believe that we have all been called here to fight for Mother Earth as brothers and sisters.

We are the Black Snake Killers.

From Chief Arvol Looking Horse of the Lakota, Dakota and Nakota nation:

"A "disease of the mind" has set in world leaders and many members of our global community, with their belief that a solution of retaliation and destruction of peoples will bring Peace.

In our Prophecies it is told that we are now at the crossroads: Either unite spiritually as a Global Nation, or be faced with chaos, disasters, diseases, and tears from our relatives' eyes.

We are the only species that is destroying the Source of Life, meaning Mother Earth, in the name of power, mineral resources, and ownership of land, using chemicals and methods of warfare that are doing irreversible damage, as Mother Earth is becoming tired and cannot sustain any more impacts of war.

I ask you to join me on this endeavour. Our vision is for the Peoples of all continents, regardless of their beliefs in the Creator, to come together as one at their Sacred Sites to pray and meditate and commune with one another, thus promoting an energy shift to heal our Mother Earth and achieve a universal consciousness toward attaining Peace.

As each day passes, I ask all Nations to begin a global effort, and remember to give thanks for the Sacred Food that has been gifted to us by our Mother Earth, so the nutritional energy of medicine can be guided to heal our minds and spirits.

This new millennium will usher in an age of harmony or it will bring the end of life as we know it. Starvation, war, and toxic waste have been the hallmark of the Great Myth of Progress and Development that ruled the last millennium.

To us, as caretakers of the heart of Mother Earth, falls the responsibility of turning back the powers of destruction. You yourself are the one who must decide.

You alone - and only you - can make this crucial choice, to walk in honour or to dishonour your relatives. On your decision depends the fate of the entire World.

Each of us is put here in this time and this place to personally decide the future of humankind.

Did you think the Creator would create unnecessary people in a time of such terrible danger?

Know that you yourself are essential to this World. Believe that! Understand both the blessing and the burden of that. You yourself are desperately needed to save the soul of this World. Did you think you were put here for something less? In a Sacred Hoop of Life, there is no beginning and no ending!"

Day 6 at Standing Rock: Life is Sweet

/About the Music: “Life is Sweet”

(co-produced by Old Gold; vocals by @frankstickemz - aka Flowzavelt)

From the musician, Cee Goods:

Life is sweet. We value our lives. They can try and attack with any means of weaponry, but it does not match the level of commitment to stopping this pipeline. Our lives are worth too much.

(The following are actual text messages I sent to Spencer (aka Cee Goods) on Sunday, Nov. 20, 2016. It was too hectic to write anything coherent.)

"Please share, protest, donate - do whatever you can do. What is happening at Standing Rock is happening to all of us... whether we realize it or not."

"I fell asleep sitting up in my car from about 430 to 630. Woke up and something was going down off in the main camp in the distance. Police cars, and a call for all the protectors to come to the bridge [on Highway 1804, which has been blockaded and closed for several weeks]."

"Police are definitely here, but it's not clear if they are the perpetrators or if it's DAPL."

"Can't get through on twitter or Facebook right now. Two planes and a helicopter circling constantly right now. Lots of people shot with both gas and rubber bullets in face and chest. People have gotten tear-gassed, they're using a water cannon to soak people and things."

"Concussion grenades and rubber bullets. Shit is going down. Someone has already left in an ambulance. There are no reporters or news outlets here."

Day 5 at Standing Rock: The Stand-Off

/About the Music: “The Stand-Off”

From the musician, Cee Goods:

How much can we take? Something has to give. We pursue with positivity, but has it reached a limit? Do we retaliate with the same energy that is received? Energy is shifting. Something is on the horizon.

We are here as protectors, not protesters. This young man threw himself down onto the tracks separating militarized police from peaceful demonstrators, a visible act of prayer.

As we eventually tried to leave the scene, however, police advanced. People were sprayed at point-blank range with OC gas -- a riot-caliber tear gas used in prisons. Women and Native elders were accosted and thrown to the ground. Many were arrested, many were injured.

It is said that capitalism becomes fascism when the government begins protecting the interests of corporations over people. We have long-since crossed that threshold. Please stand with Standing Rock to take back the power from the corrupt, morally bankrupt oil barons and give it to the people.

Our country was founded on a genocide of the indigenous people, and our legacy of "freedom" has been built on oppression and lies.

Will you stand by as our government attempts to quietly break another treaty? Will you stand by as our president-elect promises to abuse his power and double down on racist division and oppression?

Or will you stand with all people, with the Earth itself, by standing with Standing Rock?

Let's make America great again, just like it was when we found it.

Gwen Frost is a student in Bellingham, Wash. She grew up in Portland, Ore. She was sprayed in the eyes at point-blank range with OC gas by police in Mandan, ND. Why? Because she is peacefully standing up for what she believes is right, and that goes against the interests of the biggest pile of money.

Day 4 at Standing Rock: DreamsVille

/About the Music: “DreamsVille”

From the musician, Cee Goods:

What foundation is this country built on? What values do we hold true for the land? Is it all but a dream? Do we as Americans live in a fantasy world? The harsh reality is nothing is ever what it seems.

The American flag is supposed to be hung upside down only in times of dire distress. I took this photo in Camp Oceti Sakowin at Standing Rock the morning after Trump's election, but every American flag in the community had been signaling distress for months.

The Dakota Access Pipeline, or DAPL (pronounced dapple), is the source of this distress, the source of the evil that is being confronted.

DAPL is spraying the camps with chemicals from low-flying planes at night. They have donated poisoned food. They are surveilling and infiltrating the camp.

They have herded up most of the wild buffalo in the region and are keeping them in pens without food or water. Sixteen had already died as of a couple days ago. I'm sure many more have already been lost.

The protest action that makes the news is real, but it is a distraction. The police are just a pawn in this game, and the fate of Mother Earth is at stake. The real atrocities are being generated and perpetrated by DAPL, the vastly monied corporation the police are protecting at the expense of the people.

We need your help. We are under constant attack. We are in dire distress, and so is our nation. Please stand with Standing Rock today by turning your flag upside down.

Day 3 at Standing Rock: End of Trump

/About the Music: “End of Trump”

From the musician, Cee Goods:

High intensity, ready for anything. Will reach what you seek by any means necessary.

I took the above photo while wearing ear protection, eye protection and a surgical mask, standing across the railroad tracks from a row of militarized police assembled in a line to face off with peaceful demonstrators. Armed with tanks, sound cannons, tear gas, tasers, batons and guns, they flex their muscle against the people they are sworn to protect, instead defending the interests of a corporation.

They stand against the people as a symbol of capitalist greed and fear, misguided stormtroopers defending a dark empire.

Even more powerful than their terrible might and aggression is the power of love and prayer being reflected back at them. We are protecting this water for those officers, too, and for their children. And we've told them so. And then they've attacked.

We pray that love will replace the fear and that our connection to the earth and each other can overcome the divisiveness that stands in our path.

10 Days, 10 Photos, 10 Songs: An Awareness Campaign for Standing Rock

/For the next 10 days, I am collaborating on a Standing Rock awareness campaign with Cee Goods (who also happens to be my brother-in-law). He will be creating one instrumental track each day, each based on a photo I have taken at Standing Rock. This will end on Thanksgiving, because the way of life and respect for the land that the Native Americans have always fought for and tried to preserve still rings true today.

Day 1: "Dark Love"

Day 2: "K.I.N.G.S."

Day 3: "End of Trump"

Day 4: "DreamsVille"

Day 5: "The Stand Off"

Day 6: "Life is Sweet"

Day 7: "Judgement Day"

Day 8: "Diamond"

Day 9: "Major Keys"

Day 10: "Kings Return"

'We are not protesters. We are protectors.'

/I have been at the Oceti Sakowin camp near the Standing Rock reservation in North Dakota since Monday. The Native elders are the spiritual and strategic leaders here, and they have made it very clear that this isn't a protest camp, but a prayer camp. We are not here to be protesters, but protectors — protectors of sacred land and sacred water.

"This is kitchen wood. Please do not take."

The camp is unlike anything I've ever experienced. An estimated 4,000 people (with people coming and going constantly) are living in commune in the camps, which are all connected or easily walkable and sit both on Army Corps of Engineers land as well as on the Standing Rock Reservation. The camp offers medical and mental health services, daily orientations and trainings for newcomers, free in-depth legal support, media relations services, and seven different kitchens cooking and serving huge (astoundingly delicious) meals three times daily. And there's even coffee every morning, which makes all things possible.

I expected that there would be a constant protest or sit-in happening on the "front lines," that a continuous physical presence was necessary to prevent construction from continuing, but that isn't exactly the case. Last week, the Red Warrior Camp, which had been on the front lines, was raided by police, who used clubs, rubber bullets, tear gas, pepper spray and sound cannons to drive the men, women, children and elders from their homes at the camp.

I followed a plume of black smoke to its source this week and found people burning the tents and supplies that remained from Red Warrior Camp. DAPL (pronounced "dapple," short for Dakota Access Pipeline) security guards had urinated and defecated on whatever they could find — tents, teepees, blankets, even food.

DAPL continues to try to intimidate in a variety of ways. Privately hired helicopters circle the camp frequently — especially at night, when helicopters are also joined by a small plane flying with no lights. They leave the flood lights on at the pipeline work site all night long. They set fire to a hilltop just across from the camp, scorching the dry ground (right).

We are asked not to photograph and take video of any ceremony, and much of what happens here is considered ceremony. On top of that, the camp operates under "security culture," as police and DAPL security contractors are monitoring cell phone communications in the camp and interrupting cell phone service. Everyone at the camp is operating under the safe assumption that DAPL and law enforcement also have "secret agents" in the camp. (Seriously. It's real. I watched camp security chase a DAPL agent away in his car just last night. And look at this screenshot from my phone, which has given me this warning many times already.)

The weather has been beautiful, but it is already getting very cold out here at night. The last two nights I have heated large rocks over a fire, wrapped them in towels, and put one at my feet in my sleeping bag while cuddling the other. It helps. It got down to 12 degrees a couple nights ago. I fall asleep listening to the sounds of people and coyotes howling from all directions (while wearing two pairs of socks, long johns, pants, and four shirts and sweatshirts plus a hood). So, you know, it's pretty much like home.

This has already been a very emotional, unexpectedly spiritual experience. Each camp has a sacred fire that burns continuously and is meant for prayer and meditation. Only cedar, tobacco and sage, which grows wild all around the area and is used to cleanse the air as well as the spirit, can be put into the sacred fire. I have participated in a traditional water ceremony, drinking a small handful of sacred water before walking to the river to give an offering of tobacco while singing traditional songs and connecting with the presence of our ancestors. I've watched a hawk come out of nowhere to circle overhead as a young man presented a staff he had painted and adorned with feathers and symbols to represent his brothers who couldn't join him.

Almost everything that happens feels so full of meaning and spiritual significance that it's palpable throughout the camp. I have met people from every part of the country and many parts of the world. I have been told many times that if this struggle has touched you in some way, if it has tugged at you, that you have been called to be here, and that really feels true. This struggle represents the intersection of so many issues: the power of corporations vs. the power of the people, the sovereignty of indigenous people and our own respect for treaties, oil barons vs. conservationists, and the fight for racial equity, just to name a few.

I have also found myself at the intersection of my past and my present. I grew up in Fargo (where I also usually slept in a sweatsuit and socks, incidentally), but as a kid who just wanted to play baseball and run around in the sun, I could never understand why we were there. A week or more would pass each winter when the high (the HIGH) temperature never got above zero. I vividly remember a radio host laughing and telling us one day that it was 70 degrees colder outside than in our fridge. Woof.

But suddenly, Standing Rock has made growing up in Fargo "make sense." If I'd grown up where I wanted to, I would not be here today. I don't fully understand what compelled me to up and drive out here, but having been here for several days, it does feel like I was called. I don’t know what to make of it.

I'm told often to ask everyone in my own community — in other words, you — to pray, whatever that means to you, for the safety of the people at the camp and the water we are protecting. Pray that the police officers, DAPL agents and all those supporting the pipeline are moved to love and compassion. Pray for our country and for the Earth Mother, as the Lakota call her. This is more than just an issue of one pipeline. Every one of us will be affected by what is happening here.

A Letter Home from the Road to Standing Rock

/Dear Julian and Zeke,

I'm on my second day of driving. If I keep going, I should get to the camp at Standing Rock just before midnight. A corporation is trying to dig an oil pipeline across the Midwest, and it endangers the water used by millions of people. They are also trying to dig up sacred land that is protected for use by the Lakota tribe. They have been making a brave, peaceful stand for months now, and the pipeline still isn't finished. I'm going to help however I can.

I wish you could be here with me. Or that we were all going somewhere else for a different reason. Because I saw vultures today with their drooping necks and had no one to point them out to. And nobody laughed at me when I whooped out a little shriek because a hawk swooped so close to my windshield I thought he was going to grab me pull me out through the glass.

I overheard a guy in a cowboy hat tell people what he would do if he had his druthers. I saw a barn door built into the side of a hill like the Batcave. I saw horses in every combination of colors, I saw cattle and sheep grazing, and I saw a buttes and mountains frame the big Montana sky.

And I saw a train go by that just had the name "Mr. Rogers" graffitied onto its side, but without you here, I just saw it. I didn't laugh about it or try to explain why it's funny, and I won't remember it for long. Or maybe I will, since I'm writing to you about it.

Anyway, I've also had a lot of time to think. What am I doing? And why?

Even having lived elsewhere for a number of years now, I've spent about half my life in the Dakotas. But I did so through a settler's lens, and I learned and know very little about the indigenous tribes, or about the different reservations even. We did learn about "manifest destiny," though, which certainly didn't seem good or right, but it was presented to me as acceptable, so I accepted it. I was a kid. Like you are now. And I'm writing to tell you now that this is not acceptable, and it never has been.

I'm going to Standing Rock because if this happens, then things are no different than the "past" I learned about as a student. If I stay home now, then I am no different than the people whose apathy tens and hundreds of years ago looks so inconceivable now in retrospect.

I am going because I can, which means that if I don't, it's only because I have the privilege of being too afraid.

It was a clear, beautiful day today. By the time I got near Miles City, the sun had started to think about setting. I wasn't sure, but this seemed like my last best chance to get some gas and some food and some long underwear. I was anticipating a beautiful, huge sunset, and I had vague plans to stop at the side of the road to take pictures of it. But I lingered too long in town, just looking at trinkets and reshuffling things in the car, and I missed it.

By the time I had started driving again, the sun had set. I think I was nervous to start the last leg. Miles City is the spot on the map I had picked to leave the more familiar I-94, which runs through Fargo and becomes the same route I took with my family as a child when we would visit my grandparents in Minneapolis and St. Paul. Anyway, I'm turning east now because I've heard there is a police blockade on the highway coming into the camp from the north and that the road is closed.

So, I'm driving in the dark across the western edges of the prairie, through towns I haven't even heard of. I don't know what I'm going to find. I don't know what impact I can have, if any. But by writing to you, I at least feel like I understand a little better why I felt like I needed to come out here. I hope you do too. I miss you already.

Dad