The strange thing, though, was that the police were not particularly aggressive in clearing out the camp. They arrested either nine or 10 people Wednesday, depending on which report you read, and I’m told that something like 50 more were arrested the next day when the police came back through and fully cleared the camps.

The police tried to intimidate and definitely inflicted some physical injury, but all in all, the eviction was surprisingly peaceful. It only takes one police officer responding with too much force too quickly, or one person reacting too strongly to seeing his grandmother being handled by the police for violence to erupt and turn a situation like this into a disaster.

Instead, it was peaceful-ish, as policing goes. Or if peaceful isn’t the right word, well, nobody died. The police were not startlingly violent toward the water protectors who chose to stay in camp and pray until the end, which is what I was afraid of. But then, the #NoDAPL movement has never been characterized by fatal violence.

Set aside for a moment the grotesque images of water cannons, rubber bullets and explosives used by police in riot gear in Standing Rock.

During the protests in Ferguson of the past few years, militarized police frequently shot real bullets at Black Lives Matter protesters and occasionally killed them. Even when the PR risk should have steadied their trigger fingers, fatalities were commonplace. On the one-year anniversary of Michael Brown’s murder, for example, St. Louis Police shot and killed another young black man during that night’s protest.

In Standing Rock, on the other hand, through more than 10 months of steady demonstrations and consistent police confrontation, not one water protector was killed. The police inflicted serious injuries and committed atrocities, but everyone survived.

This has been on my mind for months but hasn’t been something I’ve known how to talk about, partly because I was in Standing Rock bearing witness to much of the police violence that has made the news. And it was painful and traumatic and frightening. But I also made an appearance in Ferguson, and I know that the stakes were more immediate there, though no higher in the long run.

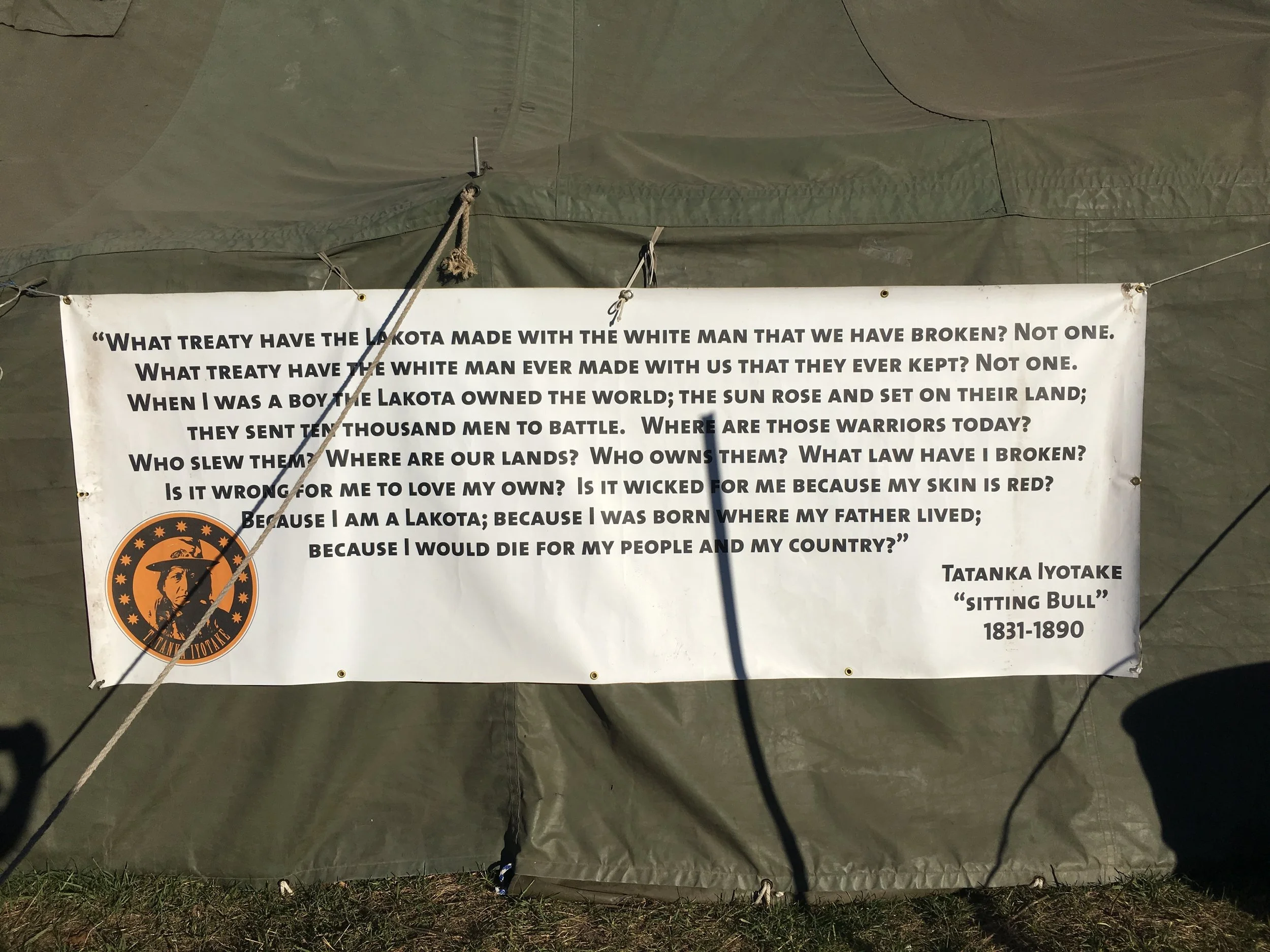

I don't know what it means. Our government and law enforcement certainly have a deep and storied history of killing indigenous people. They just haven't done that in Standing Rock yet, even as they're doing it elsewhere. Maybe it just means that our oppression of people of color has been tailored to each specific community.

Whatever the case, just as happened on Dec. 4 last year when the Army Corps under the Obama administration denied the easement needed for Energy Transfer Partners to complete the Dakota Access Pipeline, this is a time of change and transition for the #NoDAPL camps. Roughly 600 people remained in the camps from mid-December through mid-February, and only a handful of reinforcements arrived this week.

Now many of them are heading home. Many more are staying and continuing the fight on the ground in North Dakota, and a group of committed indigenous activists have promised to continue finding new sites for prayer camps to continue if needed. LaDonna Brave Bull Allard, who owns the Sacred Stone land and founded the original camp last April, has vowed to maintain a community on her own land as well, come figurative hell or literal high water.

And everyone who is leaving is leaving profoundly changed, it seems, carrying with them a sense of invigorated spirituality and an empowered sense of capability and responsibility to stand up more fiercely than ever to injustice.

Perhaps my greatest takeaway has been the interconnectedness of movements that had remained, until now, disparate. The issues being raised by #NoDAPL water protectors, indigenous rights advocates, environmental activists, Black Lives Matter protesters, immigrant rights groups, education advocates, workers' rights groups and countless others are all symptoms of the same disease, branches of a tree whose trunk contains the sickness of capitalist greed, colonial entitlement and systemic inequity.

I see the possibility for enormous breakthroughs as our passions are shown more clearly to have a common enemy, and as it becomes harder to ignore that our own liberation is dependent on our neighbor’s.

We’re all in this together — even the police officers and DAPL employees who are following orders in order to maintain an income they’re afraid to lose. Even Trump and everyone who voted for him. We are protecting this water for everyone. We are shouting for everyone’s sake that Black Lives Matter -- not just for the Black men and women who face the greatest immediate risk -- because no life is truly valued by a society that declares some expendable. We are demanding equitable access to high-quality public education because its absence leaves a cavity in our country and our communities.

No matter what you hear in the mainstream media, the #NoDAPL movement isn’t ending. It’s just shifting, dispersing, expanding. Water falls from the sky as millions of individual drops, but those beads of water don’t remain separate. They can’t help but combine, to join together as they touch, and in doing so, to become a roaring, powerful body of water.

We, too, seem like millions of individuals, but we come from the same source, whatever that is. We are intrinsically connected. And when we act out those connections, they deepen, and we awaken the potential of our unified power to overwhelm the hate and division that plagues us now.