By Keith Wain

When I was in grade school I read what I thought everyone else read: The Hardy Boys, and encyclopedias claiming to be picture books (they always fooled me). Oh yeah — and Encyclopedia Brown and Choose Your Own Adventures, and newspaper comic strips like Garfield or Family Circus.

So, three or four types of books was all I thought there was, and I didn’t think there was anything wrong with that, and I didn’t wonder if there was more.

Well, of course there was more. Judy Blume was big, so was E.B. White, Roald Dahl, and Beverly Cleary, and My Teacher is an Alien was just coming onto the scene. I didn’t read The Babysitters Club or Sweet Valley Twins; my twin brother, however, did read the Matt Christopher books, and, yes, okay, as always the classics were still being read.

So, there was quite a bit to choose from… kind of… not really… in hindsight—no, there wasn’t.

For me, reading was boring and teachers and librarians, even my parents, pointed to the same old books or boring Hardy Boys that made watching water drip in the kitchen sink look pretty cool.

I grew up in a small town (population 800) in rural northern Minnesota. We knew how to read and the school library was well kept, but we didn’t really know what was out there. We got lucky though, because compared to today, there really wasn’t much out there to read, not for us grade schoolers and middle schoolers. So we really didn’t miss much.

Today, I am a writer, a former college English instructor, and a father of three young boys aged 8, 6, and 3. I love reading and reading to my boys, and I love writing too. I enjoy these two things so much that nine months ago I started to write my own novel for young adults. I had been sketching it out on paper and in my head for a few years before I began, but I didn’t seriously write until the older two boys started school last fall. I worked on my book religiously for seven months. Now, for the last five weeks, I’ve stopped.

I stopped because I needed to sharpen my mental writing pencil (see what I mean?). I needed to write something different because I felt my writing was getting, well, dull. But I also stopped because I had been reading tons of children’s and young adult books during those same seven months. And, if you haven’t checked out what the kids have to read today you should because there is tons of it—and tons of it is very good.

Jeff Kinney, Dav Pilkey, and of course J.K. Rowling are three big names in the house right now, but here’s a short list of some other books that the boys and I have loved: The Mysterious Benedict Society, The Secret Series, The Penderwicks, The Fog Diver, A House Called Awful End, The Qwickpick Papers, The Spiderwick Chronicles, The Land of Stories, Guardians of Ga’hoole, The Miraculous Journey of Edward Tulane, I Survived, The Magic Tree House, and here are some brilliant graphic novels: The Creepy Casefiles of Margo Magoo, Captain Awesome , Geronimo Stilton, Dork Diaries, Big Nate, Bone, Sidekicks, Dragonbreath, The Flying Beaver Brothers, Stink, Emily the Strange, Amelia’s Notebooks, and Comics Squad. James Patterson even has several children’s book series; though I worry about the indoctrination of the young with his books. Just kidding. Kind of.

That’s a really short list to get you started.

I didn’t think my friends and I had that variety at our hands when we were young. And according to a Statistical Abstract of the United States by the United States Census Bureau, we didn’t; approximately 2800 to 4800 children’s books were published each year between 1980 and 1989. According to a Bowker report published in 2013, today’s juvenile book publications, between 2002 and 2013 numbers ranged from 30,000 to 37,000 each year, typically staying at around 31,000. Though the numbers I’m getting from the eighties may not represent the “juvenile” range of the Bowker report, quick observation will tell you there’s a big difference.

So what happened?! How come it took this long to get this many good books in kids’ hands? And how come so many people still go on and on about the classics as if only they can do what many of these new or newish books are doing?

Here’s what I think happened:

Education changed because technology changed. Yes, computers. Computers have determined what can be done today. Computers created different jobs and created a different pace and change in work cycles; essentially, labor has shifted greatly toward more mental work, which means if you don’t have a good education then you will have a more difficult time finding work—work that we don’t know about yet… you know, because computers change things so quickly these days. So computers really changed the way we value and think about education.

But it wasn’t just computers. It was also a general shift in attitudes towards children. We wanted our kids to be better educated and become more literate at an earlier age. Jobs were changing and other countries could compete with American education and industry. In 1983, Terrel H. Bell, then Secretary of Education, created the National Commission on Excellence in Education, which produced a report titled, “A Nation at Risk.” A brief scan of this report is enough to send one into panic over the welfare of our children. Here are just two sentences from the first two paragraphs, “What was unimaginable a generation ago has begun to occur--others are matching and surpassing our educational attainments,” “If an unfriendly foreign power had attempted to impose on America the mediocre educational performance that exists today, we might well have viewed it as an act of war.” Geez! It only gets more intense the more you read.

In 1985, the American government wanted to improve literacy. In a report by the Commission on Reading, several, now obvious, recommendations were listed to improve education and create smarter kids. A couple of the most instructive for this discussion are “Children should spend less time completing workbooks and skill sheets,” and, “Children should spend more time in independent reading.” Reports like this, though there really hasn’t been any since 1985, that remind us to provide materials that are both stimulating and beneficial to young people, seemed to have been forgotten by many of our educational institutions—but not by many parents who attended at least a good year of college.

Parents certainly wanted it too. Numerous studies show how increased reading increases intelligence. Dan Hurley, an award winning journalist and author of Smarter: The New Science of Building Brain Power, is just a higher profile example of what many of us have either experienced or observed: reading when young makes you smart.

So I think the government meant well in helping to improve literacy in America, which may have helped increase the number of books available to kids.

But, I’m sometimes wary of such commissions. After all, the government also needs to think about maintaining America as a superpower, which requires policy makers to consider who else in the world is improving, in what areas they are improving, and what the potential threats are to such improvements on said policy makers (and therefore how can the children who are human capital in a capitalist society help us). If this claim seems a little kooky, and the extreme charges against American intelligence from “A Nation at Risk” or the National Reading Commission’s report doesn’t make you wonder, look at the huge PIAAC survey done a few years ago by the Organization for Economic Co-Operation and Development (OECD). They’ll give you all the data you need on the crisis of today’s education for adults. But, then again, this organization looks a lot like those that represent the top 1% of our country, or the world. No, I’m not an expert on the OECD or such reports, but I don’t think one needs to be Noam Chomsky to feel a little suspicious.

But let’s get back to the parents. After all, aren’t they more influential than technology, the institution of education, or the government. Yes! Of course! Parents.

Parenting styles changed. Parents became more robustly involved in their children’s academic life. In the article “A Review of the Relationship Among Parenting Practices, Parenting Styles, and Adolescent School Achievement,” published in 2005 by Christopher Spera, the ultimate conclusion is that “authoritative parenting styles are associated with higher levels of adolescent school achievement.” Kristiana Blondal and Sigrun Adalbjarnardottir came to the same conclusion, in Iceland, and in the early nineties the authors of “Impact of Parenting Practices on Adolescent Achievement: Authoritative Parenting, School Involvement, and Encouragement to Succeed,” emphasize what may now seem very clear many of us.

Such studies and, in turn, the knowledge and application of their findings inevitably pushed more parents to look at and think about what their kids read. Furthermore, it implies that parents want the right books, engaging books that can elicit traits of academic success, which is typically curiosity and imagination.

And these parents who became more authoritative rather than authoritarian, sometimes complained about the school worktheir kids were doing in school, some of it being, maybe, too easy or out of date. Less than two years ago many parents in San Francisco, who were most likely more engaged in their children’s academics, demanded a better curriculum for their kids (see Dr. Susan Berry’s article “Parents of Gifted Kids Protest Dumbing Down of Curriculum with Common Core”), but this parental push for better academics wasn’t and isn’t a singular occurrence. It happened in Mankato, Minnesota ten years ago, and though we’re not experts on elementary school education, my wife and I seem to be among a growing number of parents that feel our children’s education needs updating.

This isn’t a push to privatize schools or opt for more Choice schools; it’s simply an indicator that more parents are aware of what good education looks like and they know it can be done without forms of segregation. It can be helped by good books.

So the government, good teachers, and the parents’ push for more “independent reading” and more stimulating, creative, and challenging teaching materials and practices has fed the bookstores and libraries with many more children’s and young adult books. But what about the market? Isn’t that the ultimate decision maker in publishing?

In recent years, the publishers have seen an increase in sales to parents in search of good children’s books. In an 2015 annual report by the Association of American Publishers, there are several comments like, “Parents are drawn to the format [children’s board books] since it is an effective way to introduce their children to books and reading,” and, “The children’s book clubs and book fairs market, dominated by Scholastic, have been a stable business.”

Publishers haven’t been doing too great lately, except in children’s books. In the same report by the Association of American Publishers, sales of board books in children’s and juvenile literature grew 20.2%. It isn’t all bad in adult books; adult coloring books helped offset an otherwise stale or declining adult print market. But the long term trend in children’s books looks good for publishers, and it is an strength they intend to maintain.

This is great, right? Everyone seems on board for more books for kids.

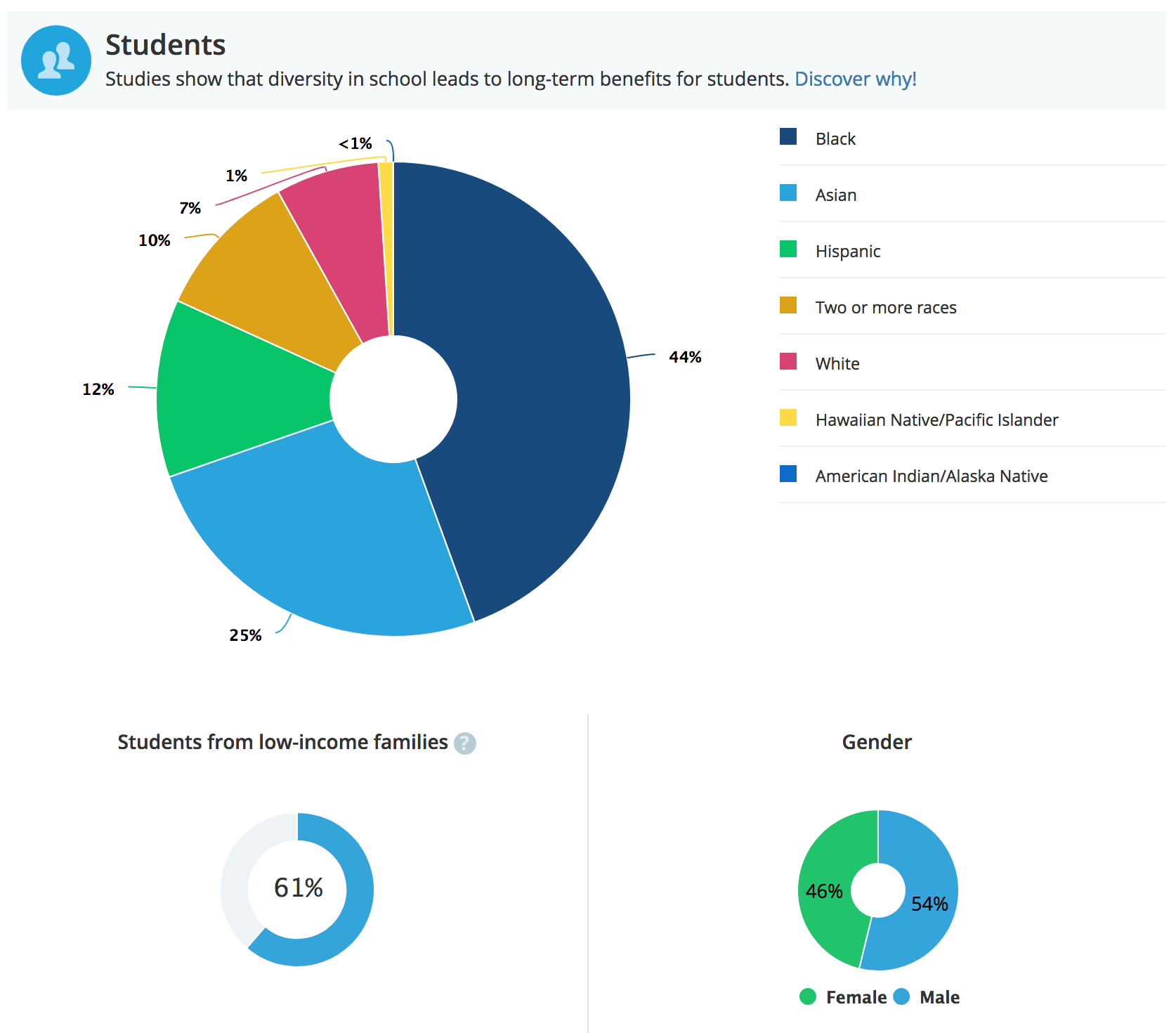

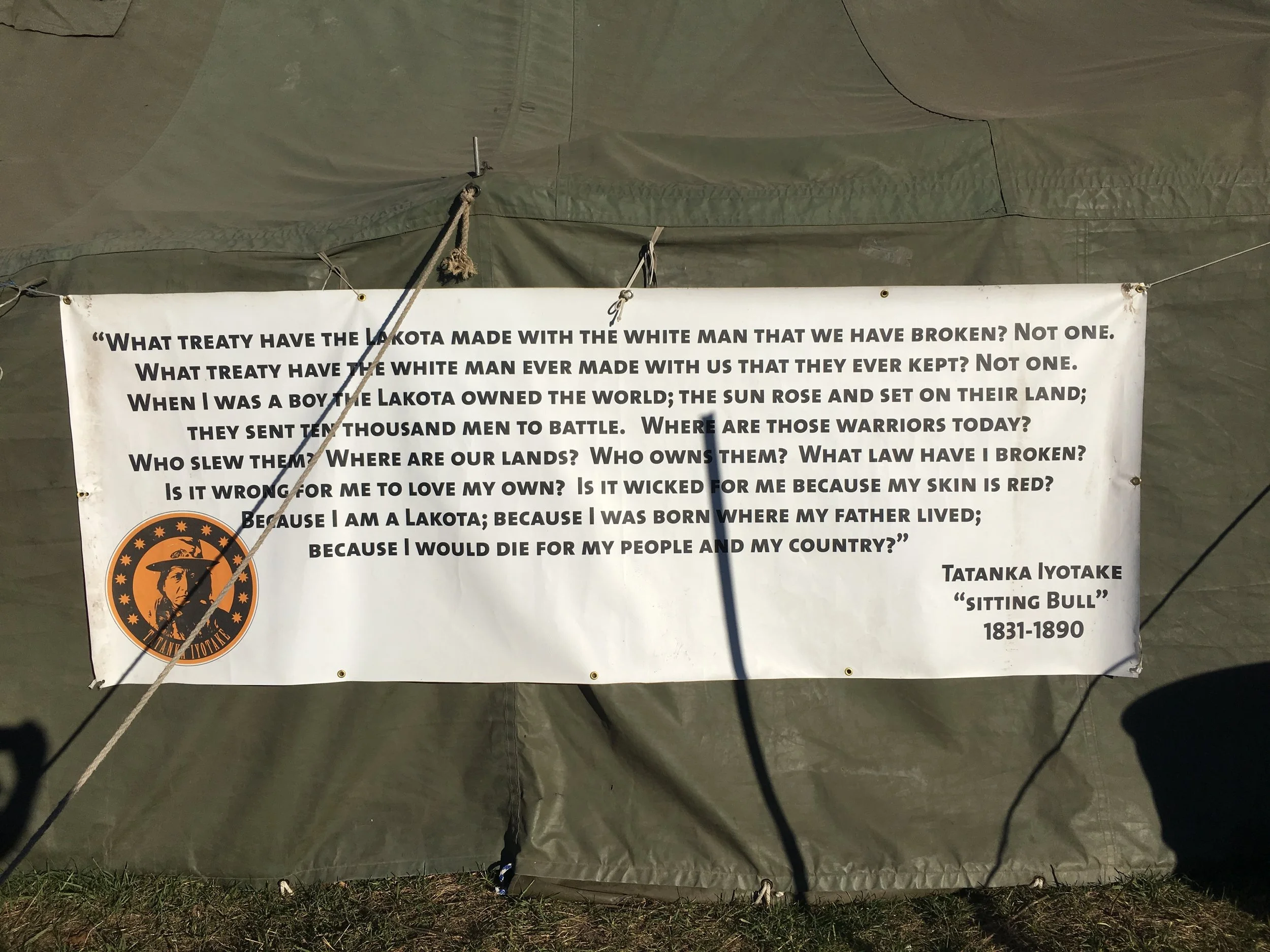

Kind of. There is a sad fact in all this. Most of these books are about white kids and represent white realities. There’s not a lot of diversity. The Cooperative Children’s Book Center out of the University of Wisconsin provides some uncomfortable statistics about who is and is not in children’s literature. So, some kids, even with over 30,000 books published each year for them, are still going to have a hard time connecting to a book.

It is getting better, though, I think. Books like The Other Boy, whose main character is a transgender boy, Forever or a Long Long Time, Book Uncle and Me, and Lowriders to the Center of the Earth all represent characters and even perspectives that are not traditionally white. And if you look deep enough, you can find great booklists on websites like Teaching for Change Books. Many of these books are not found in libraries or big bookstores.

But one last thought on why we have more great books for kids these days. Let’s go back to technology.

The internet and greatly enhanced images in video games are awesome. They can suck anyone in and keep them engaged in a story in quite profound ways. I don’t think I need to reference academic articles to convince you that video games and the internet captivate kids.

Today then, books have to compete with distractions unlike those ever seen before. “Electronics” isn’t just a Walkman anymore. Electronics is it—it’s all.

Because of all this, or at least bits of all of it, good writers and publishers know that they have to up their stimulation. The characters need to be more complicated and sophisticated, and often weirder. The settings need to be more surreal or alien or silly or simply more imaginative. But the plot needs to be much more precise, more in touch with a kid’s reality and his or her interactions with ours’. The books need to be smarter. They must not take for granted that the kid reading it isn’t very insightful or aware—or smart.

This all means that there are some excellent books for our children to read today and unless you are a moral Luddite and logical goof who thinks a kid reading about animals challenging each other in profound ways or sassy boys and girls negotiating with monsters behind their parents' backs is going to cause the pithy demise of the whole universe, you will immensely enjoy yourself and your kids will thank you.

Yes, I am still going to write my book. Yes, I am not as confident in my little story as I was before I saw what is out there today, but at least I know what I’m up against. I also realize that almost all former English teachers (high school, college, Oxford, whatever) want to write a book and be book famous. I realize I have lots of work and big dreams and lots of other people to compete against, but, hey, why not try it?

The children’s books I’ve read the last seven months have given my own writing a reality check, but more than that they have given me great inspiration to do something I would not have thought to begin but now know I can complete. Many of the books my family has been enjoying have saved me several times from today’s political mayhem. I think some of today’s authors of children’s literature are, if not geniuses, super-duper smart and extremely creative people with enviable skills. They should be remembered for their resilience against powerful people’s crummy thoughts and actions, and their guidance toward a healthy rebellion against stale idiocy. Don’t we need more of that, especially today?

If you haven’t spent some time looking into some of the many new types of children’s books out there today, if you are still hung up on The Wind in the Willows or Little House on the Prairie, or even ones like Peter Pan and Charlotte’s Web, put them aside for a while. Let the classics rest for a bit. They’re still great books, but give some of these new ones a look because I think they’ll blow your mind.